I won my first writing contest as a third grader. As the prize, I got to attend a citywide writing conference for elementary school students at our local university. I remember little about the experience except this: An adult was confused by my use of the word “tottering” to describe how a character walked in high heels. It wasn’t a word, she said; I insisted it was or, if not, it should be. (Spoiler: it is a word, and I was using it correctly.) Even at 8, words mattered to me.

I got my first newspaper byline as a high school junior writing a quite earnest and rave review of the 1985 movie, To Live and Die in L.A; I remember waxing rhapsodically about the talent of actor Willem Dafoe. By the time I graduated from Indiana University with a degree in journalism, I was editor-in-chief of one of the best daily college newspapers in the country. I spent the next 20 years as a newspaper and then online reporter, working in five cities across four states. I wrote thousands of stories and won national awards. But I never considered myself a writer.

Despite a life focused on words, despite a professional career based in writing, I did not consider myself a writer. But writing is not, and should not be considered, an elite experience only a few can achieve.

I told myself, and others, that I was a reporter first. It’s true – I loved the research part of the job, finding and talking to people, putting together a complicated narrative in a way that was easy to understand. I stressed the public service aspect of journalism since I specialized in the decidedly unflashy subject of K-12 education. I wrote for people like me, those who had grown up poor and attended public schools and who likely didn’t have the time or inclination to read through pretty descriptive passages or pretentious word choice. In truth, I wasn’t comfortable focusing on writing, so it was easier to dismiss those who did.

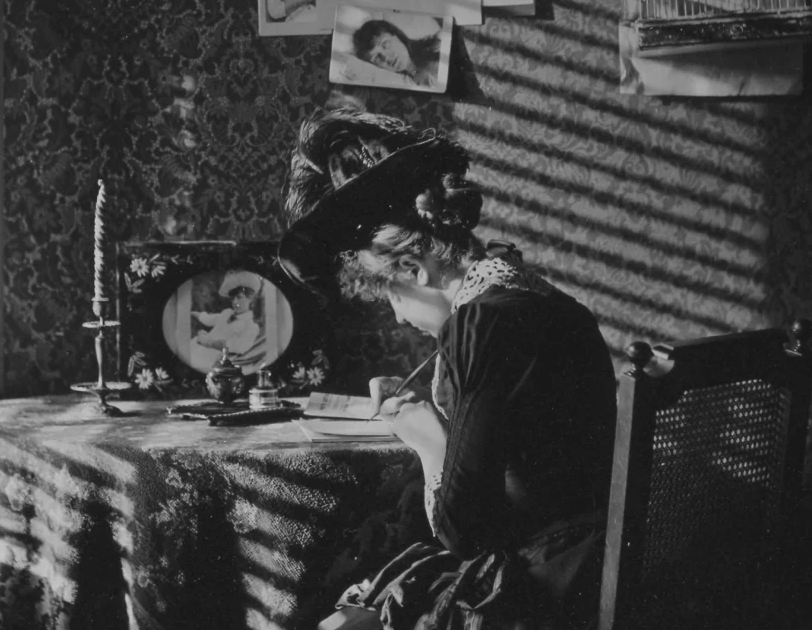

When I left journalism, I went to work for education non-profits as a communications director, which typically involves overseeing the writing of others and ghost writing for your boss. As a reporter, you’re trained to write in a neutral voice while quoting others for their opinions. As a ghost writer, you’re trying to write in someone else’s voice. I loved the challenge, but I eventually began to chafe at the restrictions. I was in my late 40s by then and finally confident enough to want to contribute to the conversation. So, I began to write, in my own time and in my own space, for me.

There is a perception that you’re only a “real” writer if you’ve sold millions of books worldwide like Stephen King or you’ve won the Nobel Prize in Literature like Toni Morrison. It’s taken me years to realize how damaging this idea is. Despite a life focused on words, despite a professional career based in writing, I did not consider myself a writer. But writing is not, and should not be considered, an elite experience only a few can achieve. If you run for exercise somewhat regularly, you’re considered a runner. If you write somewhat regularly – for yourself or someone else – you’re a writer. I am a writer. I’ll bet, if you’ve read this far, you are too.